Kinue Tokudome

(A longer Japanese version was published in the October 2016 issue of Ushio.)

The phrase that concludes Passover, “Next year in Jerusalem,” has been my wish since twenty years ago. At that time, I was interviewing people for my book on the Holocaust. I met people who devoted their lives to telling the history and lessons of the Holocaust, such as the legendary Nazi hunter Simon Wiesenthal, Chicago Mercantile Exchange Chairman Leo Melamed who was saved by a visa issued by Japanese diplomat Chiune Sugihara, and Congressman Tom Lantos who was the only Holocaust survivor to serve in the US Congress.

Mr. Simon Wiesenthal Congressman Tom Lantos

Some of them became my close friends. For them, Israel, especially Jerusalem, was a very special place. They used to ask me, “When are you going to Jerusalem?” And I would always answer, “Soon, I promise.” Then, I began working on the issues relating to American POWs of the Japanese during WWII and years just went by.

It was my meeting with Mayor Isamu Sato of Kurihara City, Miyagi prefecture, Japan that finally led to my visit to Israel. I came back to my hometown in the same prefecture two years ago and learned that Mayor Sato had helped the Israeli medical team that came to Minamisanriku, a town almost swept away by the tsunami in 2011, to assist victims. I decided to pay him a visit. Mayor Sato shared with me the fascinating stories of his having lived in a kibbutz in his early 20s and having promised that he would work to promote Japan-Israel friendship. Forty some years later, he would deliver on that promise.

Mayor Sato was told that the Israeli medical team would come as a self-contained unit so that the receiving community would not have to provide food or other necessities. Still, with the central government in disarray because of the dire situation at the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant, which was also hit by the tsumani, he knew it would be his responsibility, as the head of a nearby city, to prepare for the arrival of the medical team.

An emergency clinic with prefab buildings would be built in Minamisanriku which had lost most of its infrastructure. Electricity to run the emergency clinic needed to be generated and a supply of clean water needed to be secured. Rooms in a hotel in Kurihara City were set aside as a sleeping quarters for the medical team. Gasoline, the scarcest commodity at that time, had to be procured to run the bus carrying the team every day to the clinic.

On March 28, 2011, the Israel Defense Forces Home Front Command and Medical Corps Aid delegation arrived in the area. The team comprised a group of nearly 50 members—doctors, nurses, pharmacists, and even interpreters who spoke Japanese. The following day, they opened an advanced medical clinic featuring pediatrics, surgical, maternity and gynecological, and otolaryngology wards, an optometry department, a laboratory, a pharmacy and an intensive care unit.

Mayor Sato’s previous worries that local people might feel uncomfortable being treated by foreign doctors vanished when he saw how smoothly the medical team was treating them. After treating more than 200 patients in two weeks, the IDF medical team finished their mission. During the farewell party, Mayor Sato sang the song he had remembered a long time ago in Israel, “Jerusalem of Gold,” which was soon joined by all the members of the team.

Israeli Ambassador to Japan Ruth Kahanoff and Mayor Sato

The article I wrote about Mayor Sato was published in Jerusalem Post last year, through a kind arrangement by Rabbi Abraham Cooper, Associate Dean of Simon Wiesenthal Center.

Later, I had the opportunity to learn about the background of Dr. Ofer Merin, who headed the Israeli medical team. The more I knew about him, the more I wanted to write an article on him. Dr. Merin is the Deputy Director General and Director of Trauma Services at the Shaare Zedek Hospital, as well as a Lt. Colonel in the IDF’s Reserve Forces.

IDF has an independent medical unit that can be dispatched at a moment’s notice to anywhere around the world hit by a major natural disaster. The team headed by Dr. Merin performed medical assistance work in disaster stricken countries like Haiti, the Philippines, and Nepal. At the Shaare Zedek Hospital, he often treats victims of terrorist attacks, even terrorists themselves.

Since last year, there has been a spate of attacks, especially with knives, by Palestinians around Jerusalem. The Israel media prominently reported Dr. Merin’s work as his team tried to treat the victims as they were rushed into the trauma unit.

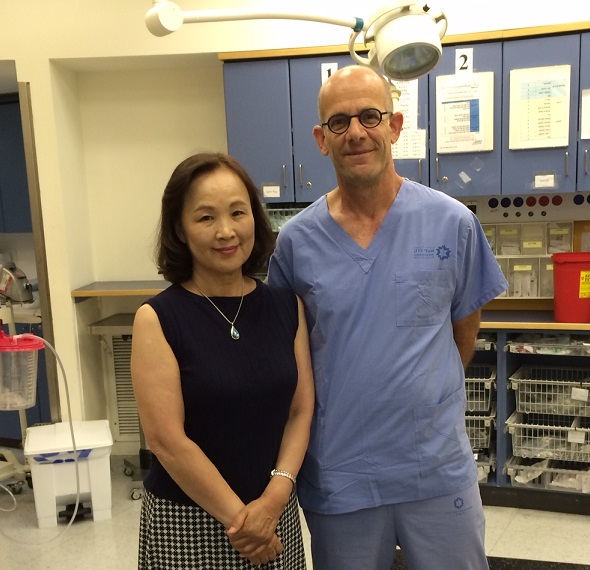

Finally, Rabbi Cooper, who is a friend of Dr. Merin’s, arranged an interview with Dr. Merin for me last June. I was praying that there would be no major natural disaster around the world or terrorist attacks in Jerusalem. And I was finally able to meet Dr. Merin at the Shaare Zedek Hospital.

Here is my interview with Dr. Merin:

Can you tell us about your father?

My father was a kid in a Jewish village in Poland during WWII. One day, they were put into a train to Auschwitz. Not all Jewish people understood the meaning of it. But his mother understood. So as the train was about to leave she kicked my 8-year-old father and his 6-year-old sister off the train.

A Christian lady found them and decided to hide them in her house. It was a very courageous decision because if anyone found out that she was hiding Jews, she would be killed. She hid them for18 months and they survived the war.

A few years later my father and his sister came to Israel as orphans. Graduated high school and went to medical school. He made a very nice career as an ophthalmologist.

He spent a lot of his time working in the third world countries, helping people. He personally opened a few eye departments in hospitals in Africa when I was 4 or 5 years old. Looking back, it must be more than just he wanted to help people in Africa. People were killed in Europe because they were Jewish. I think his going to Africa and helping people there was his way of telling, “We are all human beings. We are all equal.”

He passed away three years ago. In his last years he had cancer in his blood and was treated in this hospital. He recovered but the cancer came back. One of the doctors told him that there was a research going on for new drug that might cure him. The treatment was available in two countries, Germany and the US.

He had gone to the US many times. So he could have easily chosen to go to the US to receive the treatment. But he said, “Let’s go to Germany.” I think that was a very powerful statement for him to make. The Germans killed his parents, yet he said, “I am able to trust you. You can treat me.”

I heard that there were times that you treated terrorists.

I have to be very honest. This is one of the most difficult aspects of my work. It is very easy to stand up in a classroom and speak to medical students loudly of medical ethos that every patient is equal. That is easy. But when a terrorist who was shot and the victim he tried to kill are brought in to the trauma unit just a minute apart, you have to make a quick decision. Which one should we bring to the operating room first? Now you are standing in a position to ask yourself, “Should part of my decision making take into account the issue that he is a terrorist?” No. We treat the patient whose medical need is more urgent.

But we must also be sensitive to feeling of the victims’ family. Imagine a mother who is rushing to the trauma unit where her daughter had been brought in after a terrorist attack. What would she feel when I explain to her that I am treating the person who tried to kill her daughter first. I don’t want to tell you how many times I was stopped in the corridor by family members telling me, “Dr. Merin, are you crazy treating the terrorist first?” It is not easy to explain to the family.

We physicians are not judges. I always tell my people we should be extremely cautious for what I call slippery slope. We all share our same thoughts for murderers or rapists. But that does not mean we should treat them in different ways. Once I start judging these people who I am treating, it will never end.

You grew up in a family with a father who valued life so much, yet you are now treating people who never value life at all, even their own. Isn’t it difficult?

We don’t agree with a single percentage of whatever he is doing, but in that point of time, he is a human being. I am cautiously using this word, but I am proud that we are able to treat every patient equally.

Do you think your work, as you explained to me, personifies some aspect of your country?

When there is a disaster around the world, I receive hundreds of phone calls from those who want to volunteer. I have to tell them, “Sorry, we are all booked up.” Yes, I think it is due to the value of this country that was born because people told them, “We should exterminate you because you are Jew. We are doing the opposite. We are treating every one as equal. If you ask me if there is a connection between the reasons this state was born and what we are doing, my personal thought is, yes there is.

Rabbi Cooper asked Dr. Merin to share with us one incident in Japan that stayed with him.

For me, one of the powerful moments in Japan was the minute that you understand that you gained the trust of the people. Unlike some other countries we went to help, Japan is one of the biggest countries in the world with an extremely good medical system. So gaining their trust was not so obvious at all. The powerful moment came when people started to speak with us. Not only on their medical issues, but about their feeling and emotion. In this village we were deployed, we knew almost every person we were treating had someone very close to them die, who could be their spouse or kid or a very good neighbor. And after a few days, they started to speak with us about their emotion or about what they were afraid of. That was an important moment for me because that was when I knew we were doing the right job.

——————————————————-

After the interview, Dr. Merin brought us to the trauma unit. It was not a large room. Imagining the scene where both a terrorist and a victim are brought in there at the same time, I thought about the difficulty of Dr. Merin’s work. He was true to his belief that every life is precious. I was filled with joy of being able to meet him in person.

The Talmud, teaching of the Judaism, says, “Whoever saves one life saves the world entire.” I realized that this saying was not just an old teaching in the Talmud, but something that had been lived by people like Dr. Merin’s father and Dr. Merin himself.

Each one of us should remember those who displayed courage to save lives and learn from those who honor their legacy by their own deeds.